Supreme People’s Court is Evolving Attitude to Letters of Consent

February 8, 2016The article is published in World Trademark Review Issue 58 - December 2015/January 2016 (Article Link)

By Dan Chen, Unitalen Attorneys at Law

New draft regulations – as well as a survey of recent cases – suggest that the Supreme People’s Court is starting to take letters of consent seriously when it comes to conflicts with prior marks.

In October 2014 the Supreme People’s Court published its Draft Regulations on Certain Issues Concerning the Trial of Administrative Cases Involving the Granting and Determination of Trademark Rights for public comment. Article 20 (on co-existence agreements) states that where the Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (TRAB) refuses a trademark application, decides that a mark shall not be registered or adjudicates to invalidate a registered mark based on its conflict with prior mark(s), if the owner(s) of the prior mark(s) and the owner of the trademark at issue reach an agreement during the course of litigation and consent is given to registration of the later mark, the court may permit this. While this appears to be the first time that the term ‘co-existence agreement’ has arisen in Chinese judicial interpretations, such instrument as well as its easier substitute, ‘letter of consent’, has in fact been used to overcome *ex officio* refusals for years.

How well can letters of consent work?

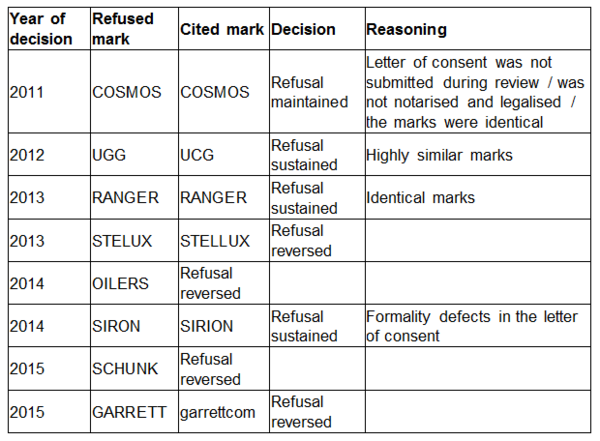

Table 1 summarises eight court decisions on administrative litigations concerning *ex officio* refusals of trademark applications which were concluded in the past four years.

Table 1

It is possible to discern a clear change in the courts’ attitude towards letters of consent in these judgments.

In both *UGG v UCG* (2012) and *RANGER v RANGER* (2013) the court sustained the refusals issued by the TRAB. In both cases it stated that the letters of consent issued by the owners of the cited mark could not exclude the likelihood that consumers might be confused. For this reason, the letters of consent were insufficient to constitute a factual or legal basis for approving the refused mark.

However, in those cases where the TRAB’s refusals were reversed, the reasoning on the impact of letters of consent is consistent. In particular, there is a feeling that where the refused mark and the cited mark bear a certain level of similarity, a letter of consent issued by the owner of the cited mark should be taken into consideration because:

· it is the most effective evidence for excluding a likelihood of confusion presumed by trademark administrative organs or courts; and

· trademark rights are a kind of civil right and trademark owners can thus handle their rights themselves, unless this involves significant public interest.

Based on this – as well as the aforementioned draft regulations – it is clear that letters of consent have become a strong type of evidence when it comes to overcoming *ex officio* refusals, provided that the two marks are not identical.

Formal requirements

The authenticity of a letter of consent is the first factor to be examined. A notarised and legalised letter of consent is usually considered a genuine expression of intent. In the administrative litigation concerning the refusal of the mark COSMO due to a prior COSMO mark (Beijing No 1 Intermediate Court [2011], Administrative Judgment 2724), the court refused to admit a letter of consent which was submitted during litigation, based on the fact that it had been written outside China, but had not been notarised or legalised, meaning that its credibility could not be ascertained.

Due to these formal requirements, it is much more straightforward to submit a letter of consent issued by a rights holder than a co-existence agreement concluded between the parties, even though the latter may appear to be more substantive. In administrative litigation concerning the refusal to register the mark SIRON due to a prior SIRION mark (Beijing No 1 Intermediate Court [2014], Administrative Judgment 2543), the applicant submitted a co-existence agreement concluded with the owner of the prior mark. However, because the accompanying notarisation document certified only the applicant’s signature and not that of the owner of the prior mark, the court refused to consider the agreement. If an applicant wishes to submit a

co-existence agreement, both parties’ signatures must be notarised and legalised.

Content requirements

In preparing a letter of consent, the following information should be clearly set out:

· the name of the prior registrant, which must be consistent with the information recorded in the trademark register;

· the name and application number of the refused mark;

· the scope of goods and services that are subject to the letter of consent;

· an explicit consent not only to the mark’s registration but also to its use in China.

In some cases the owner of the prior mark and the applicant of the refused mark may have concluded a worldwide co-existence agreement which does not list the exact application number of the refused mark at issue, since this may not have been available when the agreement was concluded. Under such circumstances, whether the co-existence agreement will be considered in a particular review proceeding depends largely on the specific terms and conditions set out therein. Rights holders should ask the owner of the prior mark to issue a letter of consent with respect to each trademark concerned based on the co-existence agreement, to avoid any doubt in the minds of TRAB examiners or judges.

Best timing

Currently, letters of consent may be submitted only as evidence in a review proceeding after a trademark application has been refused by the Trademark Office. Due to the limitations of the trademark application procedure, even if a letter of consent is provided when the application is filed, it will not come to the attention of the trademark examiners because it is not an official document and thus will not be scanned into the official database while the substantive examination is being carried out. Besides, at the time of filing, the application has not yet been allocated an application number. A letter of consent with a clear indication of the trademark number will thus not be considered to be valid.

Subject to the 2014 revisions to the Trademark Law, an examination report may be issued during the substantive examination. Theoretically, a potential blocking mark could be indicated in such a report. However, it is still unclear whether a formal refusal could be avoided by submitting a letter of consent in response to the examination report.

Therefore, the best time to submit a letter of consent is after a refusal notice has been received and a request for review has been filed.

Occasionally, it may take so long to approach the owner of the prior mark and negotiate with it for a letter of consent that the TRAB’s statutory nine-month term for concluding review cases may expire. In such situations the applicant may have to initiate administrative litigation in order to have the letter of consent considered by the court. It is a concern as to whether this new piece of evidence, which was not submitted during the administrative proceeding, would be considered during the administrative litigation. When *COSMO v COSMO* was decided in 2011, the judgment expressly indicated that the copy of the letter of consent and the translation thereof should not be accepted as valid evidence by the court, as it had not been submitted during the respective administrative proceedings or been notarised or legalised. When *UGG v UCG* was handed down in 2012, the court accepted a newly submitted notarisation and legalisation document in support of the letter of consent which had been submitted during the administrative proceedings. However, in the five cases decided during 2013 and 2015, the letters of consent were all submitted for the first time during the litigation. Although the outcomes of the five cases varied due to other factors, none of the judgments rejected the newly submitted letter of consent. Such a significant change is consistent with the Supreme People’s Court’s opinion, as reflected in the draft regulations. This is an encouraging signal and applicants of refused marks should avail themselves of all available procedures to keep applications open while they try to obtain letters of consent.